In March 2019, Tropical Cyclone Idai tore through south-east Africa, bringing strong winds and floods that killed at least 1 000 people in Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, and affected the lives of more than 3 million others. Just weeks later Cyclone Kenneth made landfall in Mozambique, causing damage estimated at US$100 million. The AfDB swore the continent would never be caught unprepared for extreme weather disasters like that again.

This September, the AfDB’s Climate Development Africa Special Fund (CDSF) announced that it would use Earth observation to bolster Africa’s resilience, launching the EUR20 million Satellite and Weather Information for Disaster Resilience (SAWIDRA) programme. As Anthony Nyong, the AfDB’s director for climate change and green growth, says, ‘we know that the quantity and quality of weather observations and forecasts fall far below the minimum level required to provide early-warning services in Africa. We are pleased that, through the SAWIDRA programme, the CDSF is bridging this gap by strengthening the capacities of Africa’s regional climate centres, and national meteorological and hydrological services’.

Scientists at NASA are already helping the cause, using Earth-observation satellite technology to monitor soil moisture and vegetation from space, observing how environmental changes affect locust populations and using the information to stop locust swarms before they start. ‘The data we have so far shows a strong correlation between the location of sandy, moist soils and locust activity,’ says NASA scientist Ashutosh Limaye. ‘Wherever there are moist, sandy locations, there are locusts banding or breeding.’ Those locations determined to be prime breeding spots can be identified and sprayed with pesticides to stop the locust population from growing out of control and destroying valuable cropland.

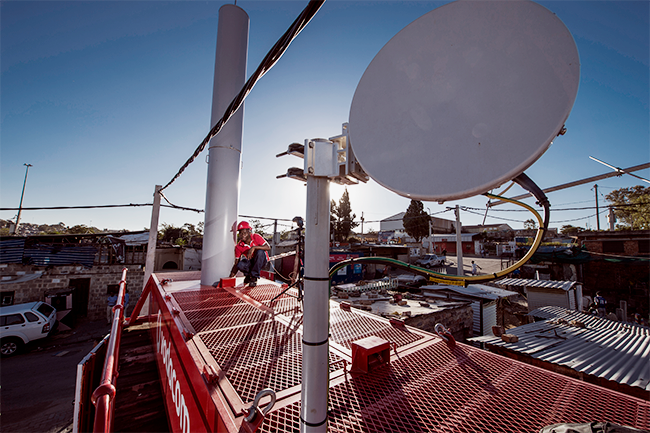

In South Africa, meanwhile, NGO Khula Education weathered the COVID-19 storm by providing satellite internet connectivity to 15 schools in the remote Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift region of KwaZulu-Natal. Satellite ISP MorClick partnered with YahClick to supply the connections, solving what – during the national lockdown – was fast becoming an education crisis as learners were unable to attend schools. ‘We can be with one school virtually even though we are physically teaching at another,’ said Khula Education director Debbie Heustice, adding that ‘some principals have even encouraged local university students to use their school WiFi to help them continue their studies online when forced to return to their rural villages when universities closed’.

That satellite internet access expanded the reach, capability and quality of Khula’s teacher and learner support, with Heustice remarking that the NGO was now achieving ‘better learning outcomes while reaching far more teachers and learners than before COVID-19’.

All of which goes some way to answering the lingering ‘why?’ in terms of the AU’s new African Space Agency. Legislation to establish Africa’s own space agency was passed by the AU in 2017, with the aim of having it up and running in 2023. In February 2020, the AU’s latest Agenda 2063 report found that in fact very little progress has been made since then.

Hence the ‘why?’. As space policy analyst Peter Martinez told Physics World magazine, ‘it might be instructive to take a step back and ask what exactly is it that the African Space Agency will do once it is established. What is its value proposition for African countries, ranging from those with established space capabilities, to those that still have to take their first steps?’ The past few months have offered more than a few clues to the answer.

In September, South African Minister of Higher Education, Science and Innovation Blade Nzimande announced the launch of the country’s Space Infrastructure Hub, to be developed with ZAR4.47 billion in funding over the next three years. The hub is part of the government’s Sustainable Infrastructure Development Symposium initiative. Nzimande hailed it as ‘a significant milestone for the South African space sector to build an indigenous space capability that will service the needs of South Africa’.

That grant will include a number of satellite builds for Earth observation and space science missions, a new ground station, an expanded data segment and new data-visualisation centre, the activation of a satellite-based augmentation system over Southern Africa, the development of products and services for use across all spheres of government, and human capital development and training. ‘The project will position space data as a tool for sustainable development, especially addressing government’s national priorities and for commercial use in thematic areas such as remote sensing, navigation, and space sciences,’ according to Nzimande.

South Africa has one of Africa’s most developed satellite industries. In early October, the Department of Science and Innovation marked World Space Week by emphasising that ‘developing a thriving satellite industry is part of government’s economic recovery programme’. But what about the stragglers in Africa’s Space Race? Again, there have been some promising recent developments.

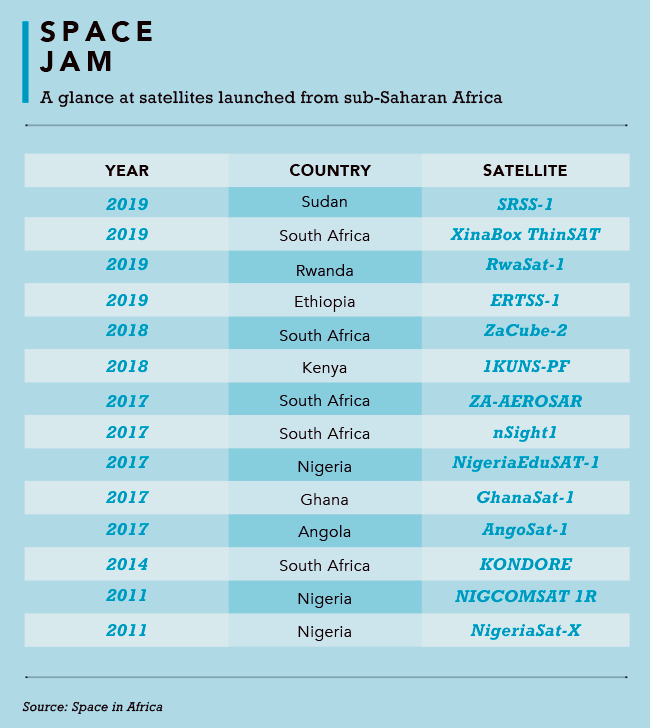

US national security newsletter War on the Rocks claims that some 11 African countries – Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Sudan – have successfully launched more than 40 satellites since 1999; while Nigeria-based analysts at Space in Africa estimate that by 2024 that list of countries will have grown to least 19, with the total number of African satellites rising to in excess of 90.

Space in Africa’s African annual sector report expects the region’s space industry to grow to more than US$10 billion in the next five years. So great is the potential for African satellites, that it specifically calls out the US for missing out on the investment opportunity.

China has been quick to seize it, though. In December 2020 Ethiopia is scheduled to launch its second remote-sensing satellite into space, barely a year after the launch of its first. Named ET-SMART-RSS, the second Earth-observation nanosatellite was designed by Ethiopian engineers in collaboration with China’s Smart Satellite Technology Corporation. The capsule cost US$1.5 million to design and develop and was partly financed by China.

The first satellite is being used for weather forecast, environment and crop monitoring. ‘The major mission of the second satellite is on flood and disaster prediction,’ director-general of the Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute (ESSTI) Solomon Belay Tessema told the EastAfrican, adding that ‘agriculture and environment are also its secondary missions’.

Tessema then outlined Ethiopia’s space ambitions. ‘The demand for satellite data is still very high and to meet the high national demands, we will launch more satellites,’ he said. ‘In the next 10 years, we will launch seven satellites including a communication satellite next year. We are planning to launch 10 more satellites in the next 15 years.’

For African countries, satellite infrastructure used to be – at best – like shooting for the moon. The massive capital investments put it beyond the reach of developing countries such as Ethiopia, Rwanda and Sudan. But in recent years, as the likes of China, Japan and Russia have invested in African space programmes and as satellites themselves have become smaller and cheaper to build, more African states have been able to enter the market. Just weeks before Ethiopia’s first satellite launch, Sudan (supported by China) successfully launched its first satellite. ‘The satellite aims to develop research in space technology, acquire data as well as discover natural resources for the country’s military needs,’ Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of Sudan’s sovereign council, said at the time.

Two months before that, Rwanda launched its first satellite from Japan’s Tanegashima Space Centre. RwaSat-1 is a 10 cm by 10 cm Cubesat weighing just more than 1 kg. It’s designed to help the Rwandan government monitor water resources, natural disasters, agriculture and meteorology.

More will follow. Criticism of African space programmes is understandable, given the continent’s urgent on-the-ground concerns related to health, poverty and education. But as Ethiopia – and Rwanda, South Africa, and many more – is learning, to find solutions to those problems, one must look to the heavens. Or, at least, to lower-Earth orbit.