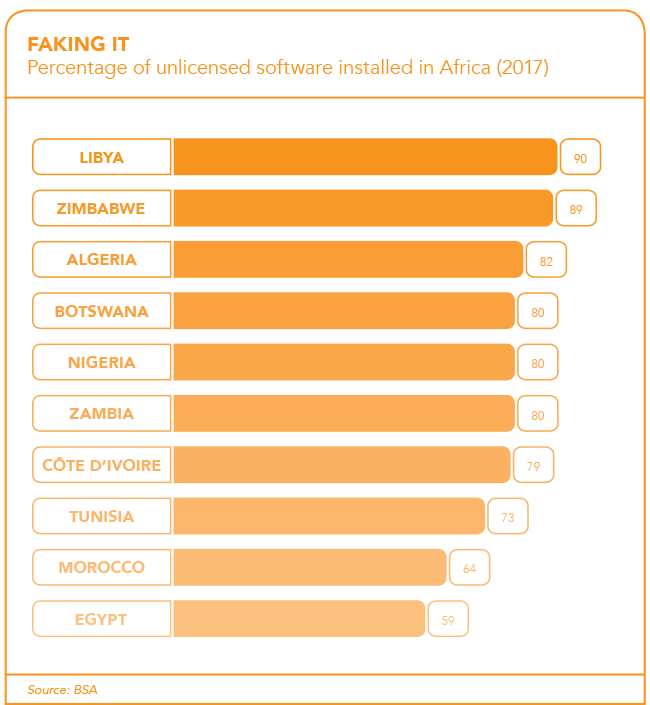

In Libya, it’s nine out of 10. In Zambia and Botswana, eight out of 10. Ditto Nigeria. That’s the proportion of computers in those respective countries that carry pirated, unlicensed or illegal software. Those statistics appear in the latest report by the Business Software Alliance (BSA), a global trade group and member of the International Intellectual Property Alliance.

In Africa, Libya scored 90% followed by Zimbabwe at 89% and Algeria (82%). In terms of lost revenue in software sales, that equals US$66 million, US$7 million and US$70 million respectively, according to the BSA.

Unlicensed software comes in different forms – one product with a single-user licence could be installed on several computers or it could be a counterfeit version. But the most popular way to obtain counterfeit software is through illegal-downloading websites.

It does not affect the IT sector directly, says Arthur Goldstuck, founder of IT consultancy World Wide Worx, but it’s an opportunity cost, as it ‘represents software that could have generated revenue. However, it also forces software developers to spend time and effort on building in mechanisms to enforce licence compliance’.

In South Africa, the rate of pirated software has declined slightly over previous years, according to the BSA. Yet, the country’s unlicensed use is still hovering around 32%, translating into a commercial value of US$241 million in lost revenue. ‘It’s mostly opportunism and cost-related,’ Darren Olivier, partner at Adams & Adams, a law firm in Johannesburg that specialises in IP and copyright law and which represents the BSA, says of the reasons why people use pirated software.

Yet while software is evolving at warp speed, efforts to curb its unlicensed use are still stuck in first gear. One of the biggest hurdles is legislation – or rather, its opaqueness. South African laws are not particularly clear on the use of pirated software. ‘The Counterfeit Goods Act needs to make its piracy provisions clearer so that it encapsulates software piracy more explicitly – and end-user liability needs to be strengthened,’ says Olivier. ‘The Copyright Act needs to be updated to make it a 21st century piece of legislation, but this is in progress.’

He adds that punishment should, where appropriate, be more stringent. ‘Software piracy represents a significant loss for everyone and should have appropriate deterrents and consequences. The Companies and Intellectual Property Commission can and should issue compliance notices that could lead to de-registration of offending companies.’

Currently, according to MyBroadBand, corporate pirates can face fines up to ZAR5 000 or three years in prison for each copyrighted item distributed if it’s a first offence. In other cases, fines can reach up to ZAR10 000 or five years’ prison time per copyrighted item. ‘Apart from the fact that unlicensed software is prone to malware and the obvious lack of support, including updates from the owner of the software, it is a criminal offence that could also expose the company and their directors to claims of reckless and fraudulent trading,’ says Olivier. ‘Needless to say, it robs the fiscus of important tax revenue that could be taxed upon the owner of the software.’

So far, effective preventative measures are few and far between. An aggressive social media campaign by BSA, says Olivier, resulted in a 13% increase in settlements paid in 2017 in South Africa. The average settlement paid by companies totalled ZAR36 094. Several companies have had to face the courts over the past few years. In 2017, South African businesses that were caught using illegal software were fined a total of ZAR5.2 million in damages, according to Business Tech. The previous year, that amount was ZAR3.6 million. These costs include settlements and acquiring new, legal software. One company opted for an out-of-court settlement of ZAR260 000.

According to MyBroadBand, the now-defunct Southern African Federation Against Copyright Theft (SAFACT) proposed in 2017 that internet service providers block access to piracy websites that offered downloads of illegal software – even sites hosted outside South Africa. Then SAFACT shut down at the end of 2018. However, the main weapon at the disposal of organisations such as BSA remains the anonymous tip-off.

Olivier says that apart from reporting companies anonymously, ‘naming and shaming’ could also add value to the fight. ‘There is a need for education and it should be part of the conversation on ethical leadership and governance. I think it is about education, good governance and respect for intellectual property rights, especially for software developers, local and foreign, [who] are responsible for much-needed innovation and access to knowledge.’

Other countries take more aggressive measures. In 2017, Phys Org reports, Beijing’s efforts included a demand for computer vendors to preload licensed software, while government agencies and state companies were prohibited from buying pirated copies. Data laws were also tightened. But despite these efforts, most of the country’s computers still ran pirated software (66% according to the BSA). In India (56% illegal), software pirates can be tried under both civil and criminal law as per its Copyright Act of 1957. With the help of police complaints, officers can seize infringing copyright material without warrants.

The implications of using pirated software are not just financial though. ‘No one wants to do business with a company that is officially dishonest,’ says Goldstuck. ‘So aside from the immediate cost of fines, it can destroy a business’ reputation.’

Companies are also especially at risk of malware attacks as valuable information can be lost or held for ransom. ‘Because it comes from an illegitimate source, there is neither a guarantee of it being safe nor any comeback or recourse if one becomes a victim of malware. Not only are you on your own, but you will find any support staff unhelpful and hostile,’ says Goldstuck. ‘The less obvious downside of pirated software is that you find yourself living in the shadows of software, always having to dodge registrations, upgrades and even security patches. This makes you more vulnerable to security incidents, but also damages your productivity as you spend so much time working around the licensing framework. What is saved in licence costs is probably lost many times over in productivity losses. Even if there are no measurable losses, you trap yourself in a shadow world where you can’t take advantage of the rapid evolution of software we see nowadays.’

For businesses trying to save a buck on software (and who isn’t?) experts point out that software asset management (SAM) programmes could be implemented to save costs. These programmes control the purchase, deployment, maintenance, utilisation and disposal of software applications within an organisation. The BSA reports that companies’ profits could increase by up to 11% with better software management.

‘It is in fact a potentially considerable asset and, if not managed correctly, a potentially significant risk,’ says Olivier. ‘Most software proprietors tend to prefer dealing with the issue of under-licensing through education and incentives for software asset management. As there is often a saving to the organisation through well-advised software asset management and/or upside for the owner of the software, the cost of proper management can be subsidised, making it an affordable option.’

Yet, even this has its problems. According to Olivier, although a government programme centred on SAM was released several years ago, ‘most companies were not aware of the concept at all’.