For many decades South Africa has had an established public-private partnership (PPP) regulatory framework that is overseen by National Treasury and implemented by various players, according to Siyabonga Mbanjwa, MD (Southern Africa) of global engineering and technology firm SENER. ‘PPPs have been used as a construction procurement model to develop a number of infrastructure and accommodation projects over the years, including toll roads, govern-ment office accommodation and hospitality projects,’ he says. In part, it’s through this model that the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP) programme was developed in 2011. The Coal Baseload IPP procurement programme is another such example. Mbanjwa says partnerships between the private sector and government are not only crucial for service delivery, but also to ensure limited government resources are utilised effectively and that financial risk to the state is mitigated.

Under round four of the REIPPP, the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) provided finance for more than 14 renewable energy developments, and it was one of the senior lenders for the landmark Sirius Solar, Dyasons Klip 1 and Dyasons Klip 2 PV projects developed by Scatec Solar. The Scatec Solar projects, for instance, were funded through a combination of equity and debt raised from the DBSA, commercial banks and local asset managers. Other notable examples are the 140 MW Roggeveld wind project, for which the DBSA provided debt funding of ZAR951 million, and the 102 MW Copperton wind project, for which the bank provided a loan of ZAR1.2 billion.

The DBSA is currently involved in 33 renewable energy projects with development investment of about ZAR17 billion. It has also created a project development facility to assist with bankable feasibility studies. ‘The DBSA remains committed to the growth of renewable energy, promotion of local ownership and community involvement, which are all crucial to long-term success and sustainability,’ said Lucy Chege, head of energy, environment and ICT at the DBSA, at a recent ceremony where it was handed the African Renewable Energy Programme Award for its work in the renewable energy sector.

Mbanjwa says government needs to create ‘the right regulatory environment’ to ensure corporates can participate in these projects, emphasising that these initiatives would not be possible without collaboration between the state and the private sector. He notes that ‘challenges during the implementation phase of a project are resolved more effectively when there’s close collaboration’ between the two sectors.

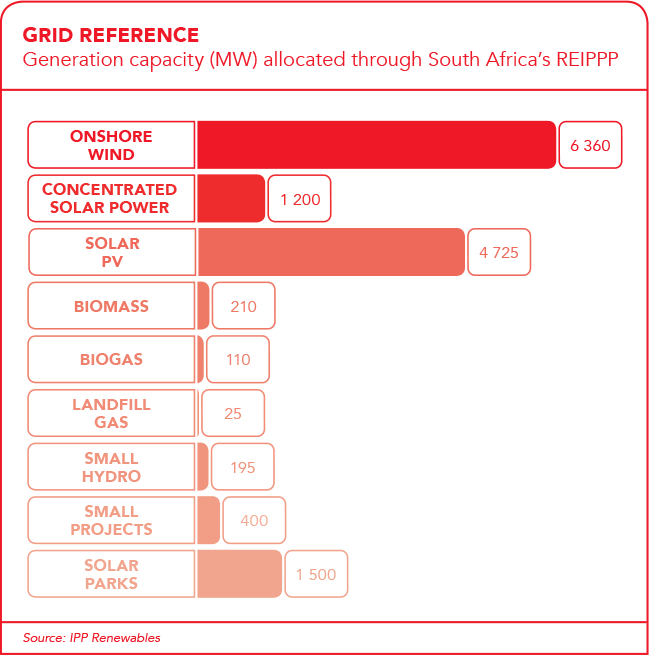

Renewable projects can vary according to the type of technology employed, the nominal power output of the project and the total development cost. ‘Technologies vary from renewable energy technology such as biomass, small hydro, onshore wind, solar photovoltaic and concentrated solar power, to fossil fuels, such as natural gas and coal,’ says Mbanjwa.

A typical network of players involved in the development of a renewable energy project involves a government department or entity along the lines of Eskom or the Department of Energy, which enters into a long-term (20 years or more) power-purchase agreement with a private party or IPP. Under the terms of the agreement, the IPP must supply power to the government entity over a long-term period, and the state-owned entity must buy this power from the IPP when it is received. This allows the buyer to provide security of supply to the consumer and businesses without spending capital expenditure or implementing the project themselves. The agreement transfers the risk of delivery – design, procurement and construction – along with financing, technology and performance to the IPP. For the IPP to deliver on such a commitment, it appoints a number of technical, financial, legal and other advisers to consult throughout the process.

Financially, these projects usually start when the IPP enters into finance agreements with lenders (financial institutions) to raise development and term loans. The loans are used to appoint engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractors to design, procure and build the power plants. On completion of the construction, the IPP appoints operations and maintenance contractors to maintain and operate the plant optimally on its behalf. The IPP is compensated through unitary payments based on the amount of net power it ultimately supplies to the government entity. The entity’s obligations to pay are secured through a sovereign guarantee from National Treasury.

The Department of Energy’s Small Projects REIPPP programme focuses on emerging smaller power developers with an emphasis on local and SME participation. The programme is aimed at projects between 1 MW and 5 MW in capacity, ranging from onshore wind and solar PV to biomass, bio-gas and landfill gas projects. The large-scale REIPPP programme includes concentrated solar power and small hydro as well as most of the technologies covered by the Small Projects REIPPP programme. The larger initiatives, which range from 11 MW to about 300 MW each, can cost from a few hundred million rands to about ZAR12 billion, and the construction period can last from one year to 36 months.

Mbanjwa explains that a fundamental difference between the traditional PPP model and how it has been implemented in the REIPPP is that, with the latter, land is always secured and owned by the private sector, while ‘in the traditional PPP model it is always in the hands of government, and the private sector is only given right of use during the construction and operations period’.

Energy technology and management company NOVO recently completed the construction of a large-scale natural gas compression and distribution facility hub in Mpumalanga, South Africa, to service mining, transportation, industrial and healthcare customers. In addition, the firm provides turnkey energy solutions to assist customers in switching to natural gas or optimising their production. It also operates two compressed natural gas facilities in South Africa to support the transportation, industrial and healthcare industries. According to NOVO CEO Andri Hugo, there are commercial, legal/regulatory and engineering components to the majority of these types of projects. ‘Novo has established a strong internal project development team that is supported by external EPC partners,’ he adds.

The size of these projects can vary from US$500 000 for customer solutions and gas delivery infrastructure to US$10 million for the gas compression distribution hubs. The larger projects such as LNG facilities are worth about US$100 million. Smaller projects take a few weeks to complete, but the larger projects typically take six to nine months, and the development cycle of the much larger projects can take a couple of years. ‘Some of these projects span over a number of regulatory jurisdictions,’ says Hugo. ‘The state’s role is critical in supporting and playing an enabling role for corporates to ensure the efficient utilisation of capital. This in return would ensure increased economic activity, job creation and a large tax base for the state. The current electricity crisis and natural gas constraints in South Africa would require very close partnerships,’ he says. This is essential to ensure the establishment of sufficient gas infrastructure to support power generation, industrial activity and transportation.

The South African National Energy Development Institute (SANEDI) is a state-owned enterprise that often works with the private sector on pilot and demonstration projects with specific applications. One such example is a collaboration with the Department of Defence (DOD) and other role players in piloting a solar thermal water project for the living quarters of soldiers serving in the national defence force.

Karen Surridge, manager of SANEDI’s Renewable Energy Centre of Research and Development, says they are currently advising and assisting the DOD with infrastructural changes required by energy-saving solutions. ‘These specific pilot projects aren’t massive, but we need to prove to the DOD and the South African National Defence Force that these proof of concepts can work,’ she says. To find a provider of the materials necessary for the project build, an open tender was put out as per the Public Finance Management Act, says Surridge. These kinds of projects follow a clear protocol.

According to Surridge, the partnership between the private and public sector in bringing these projects to fruition is very much a symbiotic one. ‘We all rely on each other,’ she says. ‘We need the private sector to deliver but they also need the public sector to enable them to deliver.’ It’s a matter of pooling resources, Surridge argues. ‘I spend a lot of time campaigning in the private sector for this kind of support. You get more bang for your buck when you pool your resources.’