Dotted across South Africa’s Limpopo and North West provinces, you’ll find three farms: Hartebeesdrift and Grootfontein, both near Lephalale; and Klipfontein, further south in the Vredefort Dome. The farmers – Peet Koen, Johan van Jaarsveld and Tania Kaiser – run a collective, collaborative partnership, pooling resources and taking full advantage of their properties’ biodiversity. But they’re not breeding livestock or planting crops on their combined 8 000 ha. Instead, they’re breeding game, including sable and roan antelope, buffalo, black impala, golden wildebeest and Livingstone eland.

‘We thought “three is better than one”,’ says Koen. ‘This way we can put all our resources together. So we farm separately but we do certain projects together as SA Game Breeders. We bought a buffalo bull together and gathered our 30 bigggest cows for that bull. We’ve done similar things with other animals.’

Koen is a founding member of Wildlife Ranching South Africa (WRSA), where he’s served as financial director and as manager of the organisation’s national auction. Like a growing number of Southern African farmers, he started out in the industry by buying a cattle ranch and converting it into a game farm. When asked why he made that transition, he shrugs… ‘Game farming is very profitable, and I’ve always preferred game anyway.’ It’s a sentiment echoed across the industry. Around 12 000 wildlife ranches have been developed in South Africa since 1991, when national laws changed to allow private ownership of game animals.

Speaking about the migration from commercial livestock farming to game ranching, WRSA president Peter Oberem says that the reasons are manifold but that it’s mainly driven by the economics and a love for wild, open spaces and conservation. ‘Clearly, the primary product of most game farms is meat. As far as game-meat production is concerned, game animals are better adapted to the harsh Southern African conditions – especially on the agriculturally marginal areas – than domestic stock.’

This is significant, given WRSA estimates that just 17% of South Africa’s agricultural land has high agri-production potential. The remaining 80% is regarded as ‘marginal’. And it’s here that game animals thrive.

‘Keeping a good variety of game animal species also ensures better utilisation of all the vegetation strata, and of the vegetation produced from the sun’s energy,’ says Oberem.

If you’ve been on a game drive or wildlife safari, you may have noticed this yourself: zebra eat long grass, while wildebeest eat short grass. Duiker prefer small forbs, while impala opt for grass and smaller bushes and lower branches of trees. Kudu browse trees up to a certain height, while giraffe eat much higher in the trees. As Oberem puts it, ‘they do not compete with each other’.

Oberem, a veterinarian who runs his own animal health company Afrivet, adds that game animals are also less susceptible to the prevalent diseases and parasites. ‘Over and above this, the cherry on the cake is the additional income generated from tourism, either consumptive – hunting – or non-consumptive. This is what makes game ranching more viable economically than raising domestic stock.’

A quick look at the region’s game farming sector shows an industry in relatively good health, despite the typical risks one would associate with agriculture. (Koen admits to being concerned about over-production and land reform – both of which, he says, are factors that have recently had a negative impact on investment.)

Oberem says that as far as employment opportunities are concerned, ‘research has shown that, on average, a game ranch hires three times as many workers than a concurrent domestic stock farm, and these employees earn on average three times as much, as the skill set needed is higher for the hospitality aspect of ranching. It is estimated that there are about 140 000 jobs created from game ranching in South Africa’.

Hunting, of course, is a big-money business at the heart of game ranching. A study conducted by North-West University’s Tourism Research in Economic Environs and Society unit (and, it should be noted, carried out at the behest of the Professional Hunters’ Association of South Africa) estimated that in 2012, hunting generated about ZAR1.24 billion in both direct and indirect income in South Africa. But hunting – lucrative as it may be – is just one of four pillars that support the wildlife ranching industry. The others are ecotourism, live-game sales and game-meat production.

Most ranchers conduct more than one land-use practice in order to diversify and make their operations more profitable. While ecotourism is of course a regular regional money-spinner (according to one WRSA report, 80% of all tourists to South Africa partake in some form of wildlife tourism), the final two pillars are robust industries all of their own.

In February 2016, an African buffalo bull was valued at ZAR176 million when a 25% stake in it was sold for ZAR44 million. At the time, it topped an all-time South African auction list that also included a ZAR11 million sable antelope, a ZAR9.7 million white impala and a ZAR7.8 million white saddle blesbok. Buffalo tend to be the most expensive animals sold in South Africa (a rhino, by comparison, can go for less than ZAR500 000), with another ‘superbuffalo’ sold on auction in September 2016 for a single payment of ZAR168 million.

The game-meat industry, meanwhile, is still in its infancy in South Africa, as numbers have had to reach a stable level at carrying capacity, and also as the country’s meat safety laws have been adapted. More than 20% of the meat consumed in South Africa is game meat, according to Oberem. ‘This meat is not only tasty, but very healthy in terms of fat versus protein content, its high mineral levels and so on.’

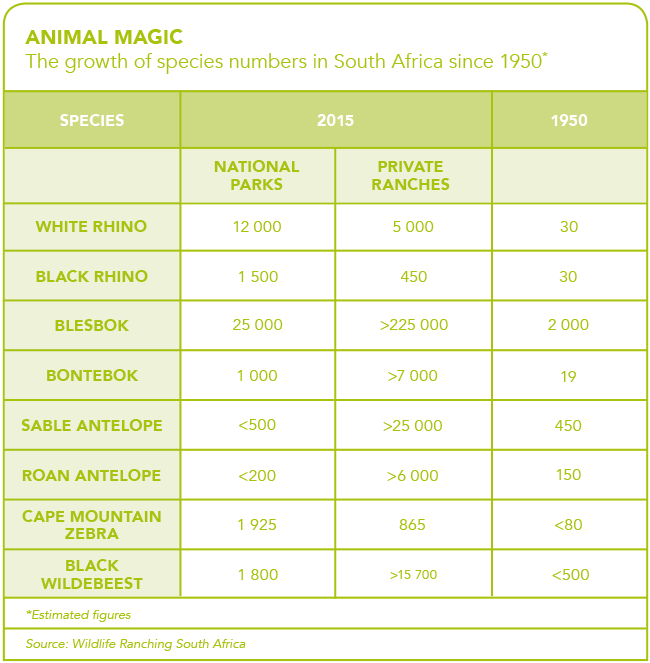

A perhaps surprising aspect of the region’s game farming industry is its contribution to wildlife conservation – despite (or perhaps because of) its focus on hunting and meat production. ‘Over the past few decades of game ranching, game numbers in South Africa have increased from less than 500 000 to almost 20 million,’ says Oberem. ‘The area covered is almost 20 million ha, or 20% of South Africa’s agricultural land.’ Independent research by the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) confirms this.

In 2016, it completed a national study on the wildlife ranching sector of South Africa, and found an estimated 9 000 wildlife properties, covering an area approximately 2.2 times greater than South Africa’s state-protected area network. ‘The majority of such ranches have been converted from livestock farms after it became more economically viable to keep and use wildlife for commercial purposes,’ according to the EWT.

In a report, Andrew Taylor, EWT trade and ranching project manager, writes: ‘Our study reiterates earlier findings that wildlife ranching is a thriving industry in South Africa and that the sustainable use of our wildlife resources can contribute important conservation, economic and social benefits to the biodiversity economy when it is practised responsibly.’

Oberem points to the ‘huge impact’ on threatened species in particular. ‘There were fewer than 100 rhino in South Africa during the 1960s, and today we hold almost 20 000 or 90%, of which 35% are on private land, of all rhino in the world. Similarly, game ranching has played significant roles in ensuring the survival of bontebok, Cape Mountain zebra, sable antelope, roan antelope – 90% of which are in private hands – and many other species, such as the geometric tortoise and the Waterberg copper butterfly. Those 20 million ha are now no longer an agricultural monoculture of crops or domestic stock, but show a far greater biodiversity than before.’

Koen sums up the situation quite simply. ‘We farm with South African products – not alien species,’ he says. ‘That’s the main thing. And because the game industry is so profitable, game ranchers invest back into their farms, whether by combating the encroachment of pests, or…’ (and here he pauses with a smile) ‘…or just because we look after our land better than cattle farmers tend to do with theirs.’